Twelve billion miles from Earth, there is an elusive boundary that marks the edge of the sun’s realm and the start of interstellar space. Voyager 2, the longest-running space mission, has finally beamed back a faint signal from the other side of that frontier, 42 years after its launch.

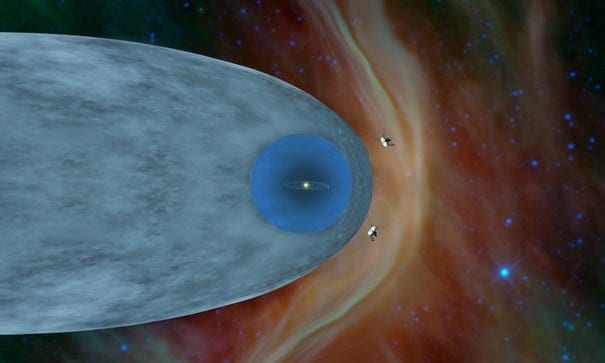

The Nasa craft is the second ever to travel beyond the heliosphere, the bubble of supersonic charged particles streaming outwards from the sun. Despite setting off a month ahead of its twin, Voyager 1, it crossed the threshold into interstellar space more than six years behind, after taking the scenic route across the solar system and providing what remain the only close-up images of Uranus and Neptune.

Now Voyager 2 has sent back the most detailed look yet at the edge of our solar system – despite Nasa scientists having no idea at the outset that it would survive to see this landmark.

“We didn’t know how large the bubble was and we certainly didn’t know that the spacecraft could live long enough to reach the edge of the bubble and enter interstellar space,” said Prof Ed Stone, of the California Institute of Technology, who has been working on the mission since before its launch in 1977.

The heliosphere can be thought of as a cosmic weather front: a distinct boundary where charged particles rushing outwards from the sun at supersonic speed meet a cooler, interstellar wind blowing in from supernovae that exploded millions of years ago. It was once thought that the solar wind faded away gradually with distance, but Voyager 1 confirmed there was a boundary, defined by a sudden drop in temperature and an increase in the density of charged particles, known as plasma.

The second set of measurements, by Voyager 2, give new insights into the nature of the heliosphere’s limits because on Voyager 1 a crucial instrument designed to directly measure the properties of plasma had broken in 1980.

Measurements published in five separate papers in Nature Astronomyreveal that Voyager 2 encountered a much sharper, thinner heliosphere boundary than Voyager 1. This could be due to Voyager 1 crossing during a solar maximum (activity is currently at a low) or the craft itself might have crossed through on a less perpendicular trajectory that meant it ended up spending longer at the edge.

The second data point also gives some insight into the shape of the heliosphere, tracing out a leading edge something like a blunt bullet.

“It implies that the heliosphere is symmetric, at least at the two points where the Voyager spacecraft crossed,” said Bill Kurth, a University of Iowa research scientist and a co-author on one of the studies. “That says that these two points on the surface are almost at the same distance.”

Voyager 2 also gives additional clues to the thickness of the heliosheath, the outer region of the heliosphere and the point where the solar wind piles up against the approaching wind in interstellar space, like the bow wave sent out ahead of a ship in the ocean.

The data also feeds into a debate about the overall shape of the heliosphere, which some models predict ought to be spherical and others more like a wind sock, with a long tail floating out behind as the solar system moves through the galaxy at high speed.

The shape depends, in a complex way, on the relative strengths of the magnetic fields inside and outside of the heliosphere, and the latest measurements are suggestive of a more spherical form.

There are limits to how much can be gleaned from two data points, however.

“It’s kind of like looking at an elephant with a microscope,” Kurth said. “Two people go up to an elephant with a microscope, and they come up with two different measurements. You have no idea what’s going on in between.”

From beyond the heliosphere, the signal from Voyager 2 is still beaming back, taking more than 16 hours to reach Earth. Its 22.4-watt transmitter has a power equivalent to a fridge light, which is more than a billion billion times dimmer by the time it reaches Earth and is picked up by Nasa’s largest antenna, a 70-metre dish.

The two Voyager probes, powered by steadily decaying plutonium, are projected to drop below critical energy levels in the mid-2020s. But they will continue on their trajectories long after they fall silent. “The two Voyagers will outlast Earth,” said Kurth. “They’re in their own orbits around the galaxy for 5bn years or longer. And the probability of them running into anything is almost zero.”

May be interested in: http://www.adhocnews.it/robins-brave-dash-across-the-sea-tracked-for-first-time/